One-handed Violinist Helps The Disabled Make Music

Monday, March 18, 2013

0

comments

{[["☆","★"]]}

The young man tucks his violin under his chin and begins to play. A

hush falls over the few spectators in the largely empty opera house, who

turn toward the bare stage. As his lilting notes float through the

room, other people trickle in from the lobby to listen.

The young man sometimes

closes his eyes as he plays, as if lost in the music. If his audience

closed their eyes, too, they would never know the violinist standing

before them has no right hand, only a stunted appendage with tiny stubs

instead of fingers.

Which is fitting, because Adrian Anantawan prefers to be judged for what people hear, not what they see.

At 28, Anantawan is one

of the world's most accomplished young violinists. He has performed at

the White House, at the Vancouver Winter Olympics, for Pope John Paul

II, for Christopher Reeve and most recently for the Dalai Lama during a private recital at MIT. Anantawan played a piece by Bach, and when he finished, the Tibetan Buddhist leader approached him.

"He put my hands

together, and put his hands around mine, and our foreheads touched for

six or seven seconds," Anantawan said. "And I'm just thinking to myself,

'My goodness, where has this instrument and music taken me?' I feel

tremendously blessed to have had experiences like that."

Anantawan's disability

has been with him since birth. Doctors think the umbilical cord wrapped

around his hand in the womb, cutting off the blood supply and keeping it

from growing properly. To compensate, he uses a simple prosthesis

called a spatula, which grips the violin bow.

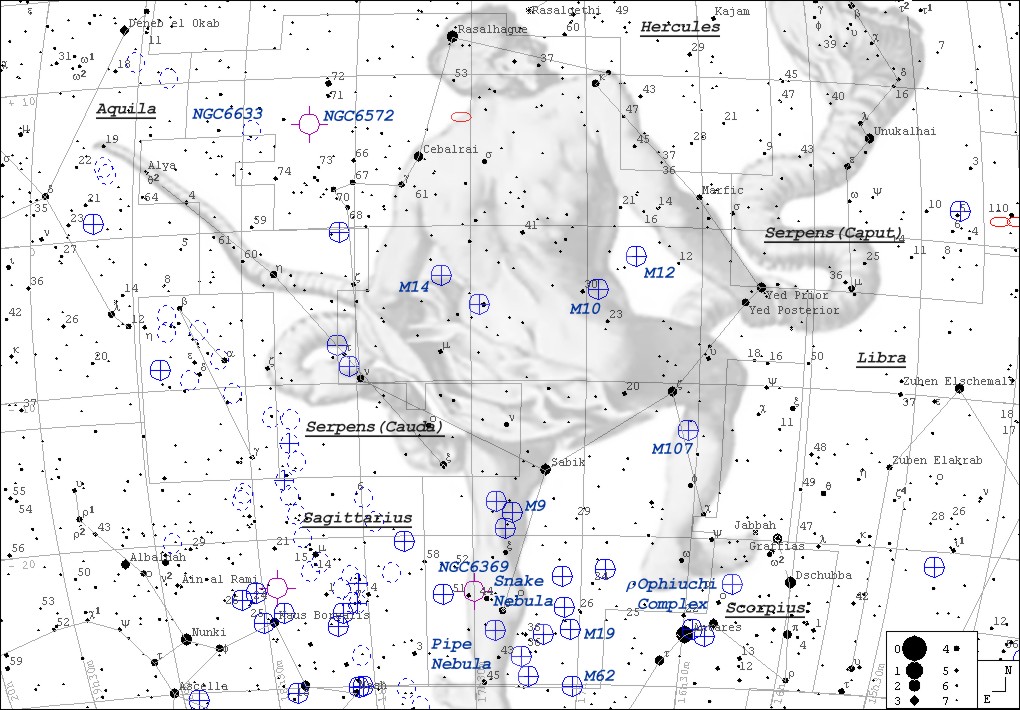

Anantawan on the stage of the Camden Opera House in Camden, Maine, where he spoke at the PopTech conference.

In recent years,

Anantawan has devoted his career to using adaptive technology -- from

prosthetic devices like his own to sophisticated computer software -- to

aid aspiring young musicians in overcoming a wide range of

disabilities. By helping them make music, he believes this technology

can help "reveal the inner humanity" of disabled children who struggle

to express themselves through other means.

"Accessibility is not an act of charity," Adrian told an audience last summer during a TEDx talk in suburban Boston, where he is now an orchestra conductor at a charter school.

"It's one of lifting the ceiling of potential development so that all

children can explore this world, but also possibly create new ones."

A 'sonic fingerprint'

Born of Thai-Chinese

ethnicity, Anantawan grew up in Toronto. With only one hand, many

childhood milestones -- learning to tie shoes, sharpen a pencil in

class, ride a bike -- were difficult for him. Classmates made him feel

different.

"Growing up without an

arm -- it seems trivial now, but when you're in grade one or two, kids

can exclude you on many different levels," he said during an interview

last fall at the annual PopTech conference in this picturesque Maine seaside town.

By the time he was 9,

his parents decided he should learn a musical instrument. The recorder

was out, because it's difficult to adapt for two hands. The trumpet was

too loud, and so were the drums. Little Adrian didn't have much of a

singing voice. So his mother decided on the violin.

His parents took the

instrument to a rehabilitation center, where they adapt prosthetics to

meet the needs of disabled children. A few months later, engineers there

produced a customized device out of plaster, aluminum and Velcro

straps. Eighteen years later, he's still wearing the same one.

"Little did my parents

know that they had invited a dying cat into their home for the first six

months in the form of 'Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,' " said Anantawan

in the TEDx talk, squeaking out the melody on his violin.

For a boy with one hand, music became a great equalizer. Suddenly, he could do something the same way as his classmates.

"I had this adaptation.

It did look different. But what came out, in terms of the sound from the

instrument, was exactly the same as theirs. And we were all trying to

make music together," Anantawan said. "Music was my way of sharing my

personality with the world. I was very shy. I didn't talk very much. And

the instrument, and playing music, helped me come out of my shell."

Adrian learned quickly.

In some ways, he was easy to teach, because instructors didn't have to

worry about his right-hand technique -- just his left hand and fingers,

which press down on the strings of the violin to produce different

notes, pitch, tone and so on.

I've had to really think, because there's no manual to (learn to) play with one hand.

Adrian Anantawan

Anantawan's educational

pedigree is impressive. He graduated from Philadelphia's prestigious

Curtis Institute of Music and earned a master's degree from Yale. During

two summers he studied under his boyhood idol, renowned violinist

Itzhak Perlman, at his residency program in Shelter Island, New York.

For Anantawan, the key to playing music is merging technique with personal expression to produce something genuine and unique.

"You're thinking, 'What

do I want to express?' and then your body finds a way to do it. That

happens with everyone," he said. "But for me, it's more explicit. I've

had to really think, because there's no manual to (learn to) play with

one hand."

As a student and a

professional, Adrian has performed as a soloist with orchestras

throughout his native Canada, at New York's Carnegie Hall and with

violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter on a European tour.

He, and others, believe

his disability produces a unique sound. Because Adrian's right arm is

shorter than that of most people, he draws the bow of his violin across

the strings at unusual angles -- not consistently perpendicular to the

strings, as most violinists do.

"With the violin, the

way that you're built physically influences to a very high degree how

you sound. I'm not able to use my entire bow, for instance," Anantawan

said. "So therefore I put more pressure on my bow to put more weight

onto the string and produce more sound. "It gives me a bit of a sonic

fingerprint."

But Anantawan's lack of a right hand hasn't limited his ability to play at a world-class level.

"There's no music he

can't play, as far as I can tell," said Professor Lee Bartel, associate

dean at the University of Toronto, who is himself a violinist. "There

are no limitations with this disability. He has fully adapted it."

Bartel has heard

Anantawan play a variety of repertoire in different contexts and scoffs

at any notion that he's gained recognition as a musician because people

feel sorry for him or see him as a novelty.

"There's no doubt he is exceptionally talented," he said. "He is a star performer."

Giving back

Anantawan says he's happiest playing music or working with children, who seem to relate to his boyish demeanor. With his place in the classical music world secure, Anantawan now wants to focus on helping others like him.

He was inspired in part by a visit years ago to Toronto's Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, which built his prosthetic. There Anantawan was introduced to a device, called a Virtual Music Instrument, that translates movement into sound.

Like a motion-controlled

video gaming system, the Virtual Music Instrument employs a camera that

is mounted on a computer screen and aimed at someone, capturing their

gestures. The Virtual Music Instrument software is designed to play

prerecorded musical samples when the person waves a hand or tilts their

head, activating symbols on the screen.

Intrigued, Anantawan

applied for a grant from Yale and gathered a team of doctors, musicians,

music therapists and educators to explore the device's potential. He

began working with a young musician, Eric Wan, who was forced to give up

the violin after a neurological disorder paralyzed him from the neck

down. The project concluded with Wan using the Virtual Music Instrument,

guided by movements of his head, to play Pachelbel's "Canon in D"

during a 2011 concert with the Montreal Chamber Orchestra.

"I had been playing the violin for about eight years before I got paralyzed," said Wan in a YouTube video about the performance. "I really didn't think I was able to play an instrument again. It's an incredible feeling."

Anantawan has been back

to Holland Bloorview several times to give concerts and talk to the

young patients. As an icebreaker, he always passes his prosthesis around

the room so the kids can handle it up close.

"There's a silence that

falls upon the room as the kids watch him play," said Tom Chau, vice

president for research at Holland Bloorview, and who developed the

Virtual Music Instrument. "He's a great role model for our clientele.

They can see, down the road, the possibilities (that exist for them)."

It's not just children

who have been inspired by Anantawan. He was once approached by an Iraq

war veteran who had lost an arm. After seeing Anantawan play in a video

online, the man made a crude prosthetic device out of cardboard and took

up the violin.

"In most of these

stories, it's never about the technique or technology that is important,

but the desire to live life authentically and creatively. We often

forget even 'traditional' musical instruments are technological

adaptations in their own right -- they are tools to manipulate sound in a

way that we couldn't do with our bodies alone," said Anantawan, who earned a second master's degree last year, this time from Harvard's Graduate School of Education.

"To say that your example has changed some life along the way for the better -- I'm extremely humbled to be a part of that."

Today, Anantawan

combines classroom teaching with the drier but no less important task of

developing arts curricula for kids with special needs -- not just

physical disabilities, but cerebral palsy, Down syndrome and other

conditions. He hopes someday to implement educational practices, working

with devices such as the Virtual Music Instrument, that can be adopted

by other schools around the globe.

"It's a lot easier to

start from the bottom up than the top down," he said. "You have to

understand where these kids are coming from, and the nature of their

disability. I was extremely lucky to find the right instrument and

adaptation and the right medium. But in public education, you don't want

luck to be a factor."

Anantawan said he's

happiest playing music or working with children, who seem to relate to

his boyish look and soft-spoken demeanor. It gives him profound

satisfaction to help open doors for kids, to help them hear their own

voice.

"The reward (for me)

comes on many levels, but perhaps the most rewarding comes in the form

of those few seconds that a child is creating something musically

unique, a voice that demands our attention," he said.

"In terms of stories,

I'm sure that at some point the children I've worked with will have

their own. But I've always found that they have touched my life in a far

deeper way than anything that I've given them."

THANK YOU FOR YOUR VISIT, PLEASE COME BACK SOON...

Title: One-handed Violinist Helps The Disabled Make Music

Written By Kristofani

Hopefully this article useful to you. If you wish to quote either part or all of the contents of this article, please include dofollow links to http://kristianporung.blogspot.com/2013/03/one-handed-violinist-helps-disabled.html. Thank you for reading this article.Written By Kristofani

0 comments:

Post a Comment